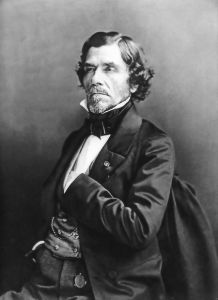

The American ex-patriot painter and printmaker, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, consciously turned his gaze toward an interest in aesthetic abstraction that he was developing during the end of the 19th century. Whistler became preoccupied with exploring the formal relations “shared” by Music and Art–specifically the primacy of tonal harmony–which the artist believed ran parallel in both Music and Art. In the early 1870s, Whistler had returned to portraiture and, when a model failed to show up at his studio one day, the artist enlisted his mother to pose for him instead. After numerous modeling sessions with his aging mother, the artist needed to compromise his initial intention by allowing her to sit in a rocking chair rather than explore a full length standing pose, Whistler painted what was to become his most recognized work of art. With this portrait painting, Whistler had succeeded in capturing “the poetry of sight”. In the 1890 publication The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, Whistler wrote:

“As music is the poetry of sound, so is painting the poetry of sight, and the subject matter has nothing to do with harmony of sound or of color.” Whistler titled this 1872 portrait Arrangement in Grey and Black No 1 and, thanks to some persuasive intervention by Sir William Boxall and other such friends in high places, Whistler was able to get this portrait accepted into the Royal Academy’s exhibition for 1872. Installed in a poorly lit and unfavorable location, Whistler’s Arrangement in Grey and Black No 1 was summarily dismissed. Today, however, Whistler’s portrait of his mother Anna Whistler has entered the public’s consciousness to such a degree that it is immensely iconic of popular taste. Martha Tedeschi has stated:

” Whistler’s Mother, Wood’s American Gothic, Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa and Edvard Munch’s The Scream have all achieved something that most paintings—regardless of their art historical importance, beauty, or monetary value—have not: they communicate a specific meaning almost immediately to almost every viewer. These few works have successfully made the transition from the elite realm of the museum visitor to the enormous venue of popular culture.”

What are your thoughts on Whistler’s primacy of tonal harmony running parallel between Music and Art?

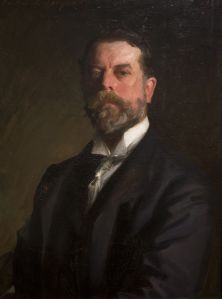

James Whistler, Self Portrait, 1872

James Whistler, Arrangement in Grey and Black No 1, 1871

Photograph of Ms. Anna Whistler, 1850s

U.S. Postage Stamp of Whistler’s Mother, issued 1934

James A. McNeill Whistler Postage Stamp, issued 1940